Introduction

The science behind sea level rise is now unquestionable: the burning of fossil fuels and other human activities releases enormous amounts of greenhouse gases which trap heat in the atmosphere and cause the Earth’s surface temperature to rise. As the atmosphere warms, ocean water absorbs extra heat and glaciers and ice sheets melt; not to mention the thawing permafrost found in Greenland and Antarctica which is releasing high quantities of methane and carbon dioxide (greenhouse gases). As meltwater lubricates the bottom of ice sheets and ice-shelves break-off, ice movement towards the sea accelerates. The extra water added to the oceans and the expanding ocean water is causing sea levels to rise at unprecedented rates.

In 2015, climate scientists working at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) revealed that the worst-case scenarios predicted by dominant climate models do not fully account for the fast breakup of ice sheets and glaciers and the melting that occurs in deep, undersea canyons filled with ice. This means the actual rate of ice melt will far exceed previous projections.

Given this new understanding of the science and acknowledging the limitations of current climate modeling to detect the full scenario of sea level rise, the question now is how quickly sea levels will rise in the future.

Increasing Global Temperatures

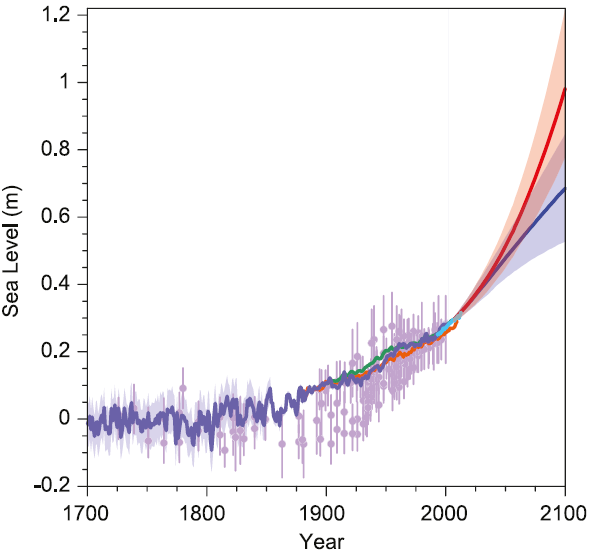

Figure 1: Past and future sea-level rise. For the past, proxy data are shown in light purple and tide gauge data in blue. For the future, the IPCC projections for very high emissions (red, RCP8.5 scenario) and very low emissions (blue, RCP2.6 scenario) are shown. Source: IPCC AR5

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Earth’s average temperature has risen by 0.8 degrees Celsius (or 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit) over the past century, and temperatures are projected to rise another 1 to 6 degrees Celsius (or 2 to 11 degrees Fahrenheit) over the next 100 years. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 5th Assessment Report predicts that with the projected temperature increase, sea levels could rise as much as one meter by the year 2100 (see graphic 1). Thus, if global warming continues unabated, we will see many low-lying coastal cities and islands disappear under water in the course of our lifetime.

COP21 in Paris

The topic of ‘climate change’ received a lot of attention in 2015 partly, perhaps, because it was the second consecutive year of highest average monthly temperatures recorded since systematic records began in 1880. The large United Nations Climate Change Conference which took place in Paris in December also concentrated minds. The Paris event brought together over 40,000 people from 195 nation states to reach a global agreement that has set the stage to solve the climate crisis. Leading up to Paris, various events and demonstrations took place worldwide. They involved civil society groups, corporations, and concerned citizens wanting to show their concern and make sure their voices were heard by world leaders.

Far from Paris, in Miami, the city where I currently reside, the events that took place to raise awareness about the impacts of sea level rise, climate change and global warming were unusually prolific. Since October 2015, I have participated in thirteen events, including the Miami People’s Climate March, the seventh annual Southeast Florida Regional Climate Leadership Summit, the 2015 Learn Green Conference, the Climate Reality Leadership Training workshop held by former Vice President Al Gore, a mock-UN Climate Event for over 200 students, and Board of County Commission meetings focusing on sea level rise, all of which highlighted the economic opportunities of a clean energy economy and strengthened the call for action.

The Paris Conference or the twenty first session of the Conference of the Parties (COP21) is part of the efforts of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) which entered into force in 1994 to oblige member states to “stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.” The Kyoto Protocol adopted in 1997 was the first guiding agreement that established internationally binding emission reduction targets which must be met by all parties through national measures during different implementation periods. The Protocol provides the architecture for future international agreements on climate change and was an important building block for COP21.

The Paris event came to a momentous conclusion committing member states to keep temperatures from increasing above 2 degrees Celsius (or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) from pre-industrial levels before the end of the century. The agreement also contains an aspirational goal of maintaining temperatures at 1.5 degrees Celsius. After more than two decades of talks and many failed attempts to negotiate a world agreement on climate change, COP21 was a success as it sets the most ambitious targets ever formalized. The agreement will likely usher in a hugely significant shift in energy policy and investment patterns favoring clean energy with zero net emissions, sustainable forestry and sustainable agriculture. But it remains to be seen whether the UNFCCC will hold nation states accountable to uphold their responsibilities in the proposed transformation of the world economy to stabilize temperatures. There is little in the agreement that is binding apart from the obligation that governments submit emissions reduction targets and action plans. For this reason it is crucial that movements and concerned citizens around the world continue to mobilize for climate justice to keep nation states true to their promise.

The Paris event came to a momentous conclusion committing member states to keep temperatures from increasing above 2 degrees Celsius (or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) from pre-industrial levels before the end of the century. The agreement also contains an aspirational goal of maintaining temperatures at 1.5 degrees Celsius. After more than two decades of talks and many failed attempts to negotiate a world agreement on climate change, COP21 was a success as it sets the most ambitious targets ever formalized. The agreement will likely usher in a hugely significant shift in energy policy and investment patterns favoring clean energy with zero net emissions, sustainable forestry and sustainable agriculture. But it remains to be seen whether the UNFCCC will hold nation states accountable to uphold their responsibilities in the proposed transformation of the world economy to stabilize temperatures. There is little in the agreement that is binding apart from the obligation that governments submit emissions reduction targets and action plans. For this reason it is crucial that movements and concerned citizens around the world continue to mobilize for climate justice to keep nation states true to their promise.

What is different now compared to seven years ago when a global climate agreement was in negotiation at Copenhagen and nation states failed to come to a consensus?

Growing Active Citizenship

For the first time in history we are now witnessing a more generalized acceptance of the science behind climate change from diverse groups. Moreover, efforts to reach a worldwide consensus on global warming show that world leaders and governments are listening, and understand that we need to act now and unlock the necessary investments to contain global warming. Many media outlets point to the important role of civil society groups and concerned citizens who came together in Paris to demand climate justice through various channels, including the inspirational initiative of people taking their shoes off when not allowed to march due to the security concerns in Paris. The various movements for climate action are gaining force because people are now personally experiencing the impacts of increased flooding, droughts, storm surges, stronger hurricanes, etc. and are speaking up to put pressure on governments to do something about it through policy change. Furthermore, the severity of climate change is now understood by the youth who are insisting that this generation has a moral obligation to pass on to future generations a world that is livable. As was explained by a fifteen-year old Aztec student at the UN General Assembly in July 2015, we cannot pass on the harmful consequences of our actions.

Change is already happening and I do not doubt that the new agreement reached in Paris and the investments that will be made will help the world’s transformation into a sustainable economy. The questions that remain is at what rate does societal and economic change need to occur to affect the root causes of melting glaciers and ensuing sea-level rise? What solutions do we need to implement to solve the climate crisis? And will advocacy and active citizenship help to keep the momentum around climate action strong until we see global emissions curb?

Climate change risks are currently in focus both internationally and here in Florida and various proposals for effective solutions are being made. In Miami-Dade County, we are hearing from experts on mitigation and adaptation solutions, education, nature-based solutions, as well as a carbon-tax initiative. I invited these subject-matter experts to outline their proposals below to motivate action and learning about adaptation and how to solve the climate crisis.

Solutions and Adaptation-Methods to the Climate Crisis

Revenue-Neutral Carbon Tax – by Greg Hamra, Citizens’ Climate Lobby

Experts the world over realize the most effective and efficient solution to reducing emissions from fossil fuels is a price signal, a price on carbon. The most politically viable solution is a revenue-neutral price carbon tax assessed at the most upstream point of extraction — the mine, the well-head, the frack-pad — based on the material’s carbon content. The money collected is returned to taxpayers in some form. Support for this market-based solution is surprisingly strong. Seventy four countries, 23 sub-national jurisdictions, and more than 1,000 companies and investors expressed support for a price on carbon in advance of COP21. During the week of COP21 we heard Elon Musk, Bernie Sanders, and ExxonMobil pledge their support for a revenue-neutral carbon tax. Prior to this, six big oil companies and six big banks expressed a desire for carbon pricing. Three former cabinet secretaries — George Shultz, Robert Reich, Steven Chu, a number of Nobel Economics Laureates and other thought leaders all support a revenue neutral carbon tax. Even the godfather of climate science, Dr. James Hansen, supports a carbon fee and dividend. Sec. Shultz likes to say: “You shouldn’t call it a tax if the government doesn’t keep it.” The fee and dividend plan returns all monies collected to American households in the form of a rebate check. This model carries numerous benefits, is considered the most equitable and would improve the economy and create millions of jobs.

Environmental Education – by Caroline Lewis, Executive Director of The CLEO Institute

An informed and engaged public is essential if we are to slow the escalation of climate disruptions and their effects on humanity and biodiversity. Our elected, business, and community leaders need to know that: (a) we understand climate science, seriousness and solutions; and (b) we expect them to act in the public’s interest and keep us out of harm’s way.

Just about every climate panel, forum and summit highlights the need for greater public awareness of the climate crisis, and huge numbers of education and outreach practitioners respond. We heed the call, providing classes, courses, programs, science cafes, film screenings and such to engage the disengaged. But we have to do more – much, much more – to reach the masses, from K-to-Gray.

We must deliberately set this climate agenda and significantly increase funding for school and community outreach, including: professional development, innovation centers, programs, contests, symposia, panels, workshops, showcases, and forums for interdisciplinary and intergenerational climate education and engagement.

In schools, certain science classes address the topic, but there are too many missed opportunities to tackle climate change in math, language arts, social studies, art, and just about every subject area, and in assemblies, debates, poster contests, PTA meetings, etc. Students, teachers, parents and the public at large deserve to know and be engaged in advocating for a more climate resilient future.

Miami, with a population just over 2.6 million, is often referred to as ground zero for climate disruptions because of: sea level rise; saltwater intrusion; freshwater depletion; ecosystem fragility; infrastructure vulnerability; prolonged heat waves; changing health patterns; rising insurance rates, and more. And the most vulnerable among us will be the most affected.

Climate change is a complex issue, but it can be simplified for a lay public in novel ways through well-funded education and engagement efforts. Knowledge in this case is indeed power. Climate scientists have affirmed that, with business as usual, we are creating a hostile world where humanity and biodiversity as we know them cannot thrive. Elected and business leaders must act, and an informed and engaged public will make sure they do.

Local Mitigation/Adaptation Efforts – by Yanira Pineda, Sustainability Coordinator of the Environment & Sustainability Division, City of Miami Beach

Miami Beach is taking a leadership role in establishing effective long and short terms solutions to address one of our world’s toughest challenges: preparing for the future uncertainties of our changing climate. Its geographic location and low-lying topography makes this coastal municipality inherently vulnerable to flooding, storm surge, and other environmental impacts. As part of its resiliency efforts, adaption and mitigation solutions have become critical.

Miami Beach is adapting to sea level rise by updating their existing gravity-based stormwater system with tidal control valves, pump stations, and other innovative drainage improvements. Pump stations and raising roads serve to keep streets dry by quickly expelling rainwater and elevated groundwater from urban areas. The City is also amending the Land Development and Zoning Codes to establish standard base flood elevation, higher minimum finish floor elevations, and minimum elevations for public and private seawalls.

Natural infrastructure is also a major component to Miami Beach’s adaption efforts. The City’s beach and dune system provide natural buffer to protect the City from storm surge and erosion, while also providing natural habitat for migratory birds and nesting sea turtles. The City is also developing a robust urban reforestation program to increase the City’s tree canopy, reduce heat island impact, capture stormwater and create a more walkable city.

Conservation – by Greg Guannel, Urban Conservation Director, and Chris Bergh, South Florida Conservation Director, of The Nature Conservancy

South Florida’s coral reefs, beaches, mangroves, forests and freshwater wetlands are well known for the critical habitat they provide for native plants and wildlife. They are also understood to be a big part of the diverse mix of attractions that anchor the region’s tourism and real estate-driven economy, and our quality of life as residents. Can they also be part of the solution to climate change? The answer is an emphatic “yes!” By preserving and restoring vegetated natural areas – and even planting trees in the heart of the city – we ensure that plants can do what they do best; pull carbon pollution out of the atmosphere and turn it into something beautiful. Nature conservation is relevant to people at every scale, from the heat reduction benefits provided by that single tree in the urban core, to the protection from wave action provided by individual coral reefs, dunes and mangrove swamps, to the safeguarding of our primary source of fresh drinking water, the Biscayne Aquifer, by restoring the massive Everglades Ecosystem. The better we protect remaining natural assets, the faster we restore natural areas damaged in the past and the more creative we can be in integrating new naturalistic features into the built environment, the better off we, and countless other species, will be. Taking care of nature in South Florida helps nature take care of us.

Articles of Interest

Bradford, A. (December, 2015) What is Global Warming. Live Science. Found in the World Wide Web link

Ghose, T. (August, 2015) NASA: Rising Sea Levels More Dangerous Than Thought. Live Science. Found in the World Wide Web link

Goldenberg, S. et al (December, 2015) Paris Climate Deal: Nearly 200 Nations Sign in End of Fossil Fuel Era. The Guardian. Found in the World Wide Web link

Goldenberg, S. (January, 2015) 2014 officially the hottest year on record. The Guardian. Found in the World Wide Web link

Hill, T. (December, 2015) Report: The World Will Run out of Breathable Air Unless Carbon Is Cut. Take Part. Found in the World Wide Web link

IPCC 5th Assessment Report. Found in the World Wide Web link

IPCC (2013) IPPC 5th Assessment Report: Summary for Policy Makers. Found in the World Wide Web link

Real Climate (October 2013) Sea Level in the 5th IPCC Report. Found in the World Wide Web link

UN Foundation Board (December, 2015) Now We Must Move with Urgency to Deliver on Promise of Climate Agreement. UN Foundation. Found in the World Wide Web link

Valdmanis, R. And Jarry, E. (December, 2015) How the world learned its lesson and got a climate deal. Reuters. Found in the World Wide Web link

Vaugham, A. (September, 2015) US science agency says 2015 is 97% likely to be the hottest year on record. The Guardian. Found in the World Wide Web link